Forest restoration in areas invaded by Pteridium aquilinum ferns

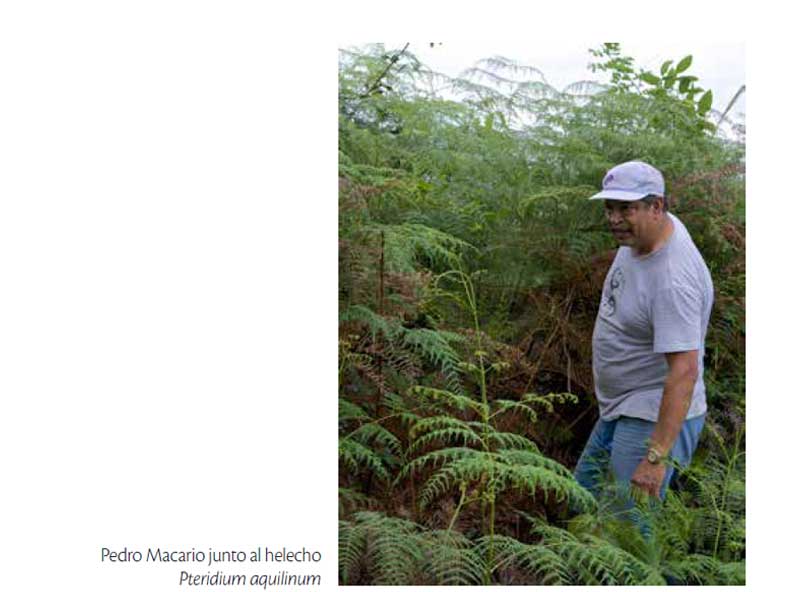

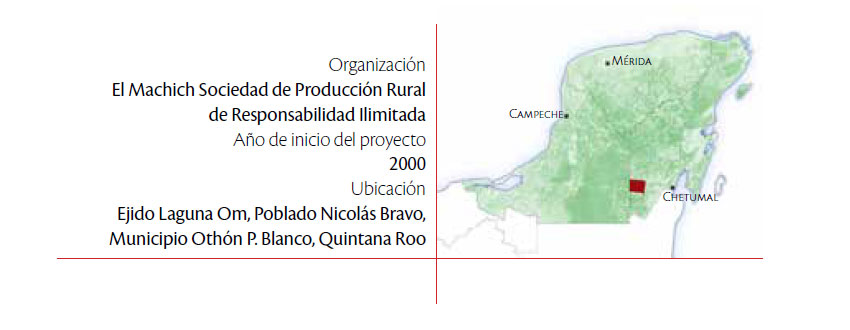

Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn, (fern, cilantrillo, crespillo, warkan, xtok' xiw) is a fern with worldwide distribution that has developed an amazing ability to survive, because once it colonizes a pasture or agricultural area it is very difficult to eradicate, the soil practically becomes unusable and producers end up leaving the area. The solution to this problem has been, from the beginning, one of the concerns of the society of producers called El Machich. This association was formed in 2002 by thirteen ejido dwellers from the Laguna Om ejido which focuses on forestry, agroforestry and beekeeping. The group leader is Pedro A. Macario Mendoza, ejido dweller and researcher at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR), with ample experience in the ecological study of the stages of forest succession. Among the plots at "El Machich", Macario conducts research on secondary growth, management of acahuales, enrichment of the forest, and certainly forest restoration in areas invaded by the fern, a field of study in which he has become an authority. Initial situation"In 1992, says Macario while he walks through a forest that appears to be a few decades old, this was one deforested hectare. We started to make enrichment of acahuales with mahogany and cedar trees and today they already have buttresses and an average of 30 cm in diameter… it is amazing how they have grown!". "Enrichment, he explains, is necessary so that management of secondary forest is economically viable, because a cubic meter of any kind of wood, be it tzalam, chacah, etc., other than mahogany, cedar or ciricote is currently sold at the local market at 1,600 pesos; while the total cost to extract the cubic meter is 1,500 pesos. If we enrich with mahogany or cedar the panorama changes, because the cubic meter of this species has a current price of 5,000 pesos with the same extraction cost of 1,500 pesos. "Acahual enrichment is not a plantation where there is only one species, yet it is about planting species of value in the forest with natural growth". In this way, and while showing his plots of 15, 21 and 29 years of secondary growth, Macario explains the beginnings of his research on enrichment and diameter growth in acahuales.

Later Macario shows a remnant forest of 50 years, and marks a zapote (Manilkara zapota) of over 100 years, a survivor of the logging that took place in the 70s. "This is a sign of what this area of forest is to become", explains with the passion of a great teacher. "This remnant islet trees are over 50 years with jobo (Spondias mombin), zapote (Manilkara zapota), copal (Protium copal) and palms such as guano kum (Cryosophila argentea) that are typical of the rainforest". Macario argues that these 200 hectares, in accordance with "El Machich", are intended to show other peers in the ejido and whoever is interested, that restoration is possible and only requires will, advice and a few pesos, of course.

It could be said that the key moment is when, after 15 years of having started with the treatments, we see that the restoration has worked out and the fern has been controlled. "This plot has already been five years without burning (witness plot)", says Macario while lifting a biomass mattress from the soil made of dry ferns. "And this one also has another five years without burning (plot with treatment), with not so much combustible materials and grasses already beginning to dominate". The dry biomass is very flammable, but the fern has underground rhizomes which do not die with fires, and within weeks it sprouts again. That is their strategy to dominate the space, everything else dies but the fern. "There is only one thing that inhibits the growth of ferns, and that is shade. So if the vegetation grows, the fern stops growing; it does not disappear, but it ceases to invade. The problem is that the forest takes too long to grow and the ferns are burnt frequently, that's why they dominate if there is no treatment or intervention".

The question is how to accelerate the succession process without the fern winning? "In the literature you can find some control methods that have been tested, but none of them mentioned the slashing which is what we propose", Macario said. "The problem with the classical methods of control is that they all assume that after fighting the fern agriculture will come; that is, a change of use that includes restoration, and that is why they mention the plow and harrow to expose the rhizomes to the open air, or roller to crush the fern… others mention herbicides, but this is not good if we want to allow the vegetation to regenerate again".

"This other forested area has 15 years of treatment, he explains, and some ferns are still seen, dimmed as a rhizome, but it does not disappear. This lot went from fern to acahual, and is now a secondary forest enriched with cedar and mahogany". It is amazing that when starting the treatment, the acahual begins to grow with over 40 tree species that colonize it. That means that the fire does not kill their seeds and their vegetative parts, but rather the fern does not let them grow. We believe that these species already have "adjusted" to the incidence of fire. "Today we can say that we have a clear control method for the fern Pteridium", Macario explains. "Regardless of the investigation, says Macario, what we are looking for is how to finance new areas of restoration. Right now we are watching over 50 hectares with 5 years of treatment, so now an annual treatment is needed; but this step is critical because if it is abandoned, the fern will invade again, it is not yet sufficiently covered by shadow". Macario with pride and passion tells that "he saw this restored area (with 5 years of treatment) when it was a fern field almost 50 years ago, and often dreamed of restoring it. Now I see my dream come true, of course with the support of my colleagues in El Machich, the National Forestry Commission, the National Council of Science and Technology and ECOSUR; we all contributed with will, advice and various pesos. The mission is still not accomplished, we need to continue for 10 years and then start another long way for the use or management of the area... that is the lesson that follows". "Legally there is no difference between a mature forest, with great forestry potential, and an acahual. This creates a perverse incentive, says Macario, because the use of an acahual is not as profitable as a well-managed forest. However, since a 10-year acahual is a forest according to law, inventory and management plans are needed, and they are very expensive". Given this scenario, the most common choice among producers is to fell and make milpa or pasture. "In Calakmul, he explains, we are doing a technical study on acahual management, and next to that we are working with specialists to propose an amendment to the forest law". The will to make a change is there, what is difficult is to define what an acahual is and at what point it ceases to be that and is considered a forest. This change could make a big difference in land use, because if you could reduce the cost of managing the acahual, in the third year farmers could make a profit and would have an incentive to begin to recover or restore the forest. If so, the restoration of degraded forest areas would become economically viable. |